In the early 2000s I was contacted by Ernie Luck a collector and researcher of Mason's pottery who had been looking into a vague connection he had heard of existing between Captain E. J. Smith of the

Titanic and the Mason and Spode pottery dynasties, a link he had gone on to substantiate. As well as providing me with much other information that helped me in my own research, Ernie subsequently sent me the following article detailing the Smith-Mason connection which he had written for the Mason Collector's Club newsletter in 2003 and he has kindly allowed me to reproduce it here in full.

Elizabeth Smith (1855-1942) was the eldest of nine children born to Captain Smith's uncle George and his wife Thirza nee Leigh, and though her own story is nowhere near as glamourous as that of her famous cousin it is nevertheless an interesting piece of local history showing the connections - though often distant and accidental - that could build up between disparate families in such a self-contained region as the Staffordshire Potteries once were.

----------

Charles Spode Mason and his Descendants

by

Ernie Luck

Charles Spode Mason was the only son of Charles James Mason’s marriage to his first wife Sarah Spode. I have been unable to trace a record of his birth or his christening, but a consensus of the age attributed to him on various documents suggests he was born in 1820 or 1821.

Despite the ultimate bankruptcy of the business, his father Charles James was, by and large, a very wealthy and successful business man. By contrast Charles Spode Mason appeared to have none of these attributes. This may have been due to his privileged upbringing leading to slothful ways, or maybe Charles James was too busy with the business to ensure his son applied himself to his education; whatever the reason, the evidence, gleaned from a variety of sources suggests that he had neither a successful marriage nor a successful business.

Charles Spode did not get married until 1856 – the year of his father’s death – when he was 35 years old. He married Elizabeth Leese, a sixteen year old, at St Paul’s Church, Stoke on Trent, on the 21 September. Their only child, Mark Spode Mason, was born on 11 Feb 1858 at Terrace Buildings, Fenton. Incidentally, Terrace Buildings Works was one of the lesser known Mason manufactories which, according to Reginald Haggar, was built by Charles James in 1835 and vacated in 1848.

Although Charles Spode was described as a Solicitor on his marriage certificate, the 1861 census return tells a different story because on that document he is described as having ‘No profession or trade’. But it is the transcript of a letter held in the Haggar Archives which provide a rather damning insight into his professional status. The letter was written in July 1933 to J. V. Goddard from a Mr J. Beardmore. He writes ‘Midway between 1860 and 1870, it was intended that I should study law, and I was for a time in the offices of a firm of lawyers, and Mr Charles Mason called several times, a ‘wreck’, the butt, I fear of the clerks who spoke of him as a ‘broken down solicitor’, meaning perhaps ‘not legally qualified’’. Things must have continued to go down hill for Charles because when he died in 1878 at the age of 57 years, he was a resident of the Stoke upon Trent Workhouse.

My research of Charles’s son Mark Spode Mason was only accomplished with the assistance of his great-granddaughter Mrs Marjorie Burrett, who lives in East Yorkshire and a distant relative who lives in New Zealand (one of the Quaker Mason’s). Without their prior research, progress would have been slow, if not impossible. Although their research was accurate in essentials, the devil lay in the detail and my efforts to put some ‘meat on the bones’ proved to be not as easy as I had anticipated. With two children born out of wedlock, his propensity to move frequently, and his use of ‘James’ as a first name, trying to find him or the family on the census was a researcher’s nightmare.

Mark married Elizabeth Smith at St Giles Church in Newcastle-under-Lyme on 23 April 1877. Elizabeth’s younger brother and sister, William and Emily were the witnesses. Elizabeth was connected with another famous person; she was a cousin of Edward Smith, Captain of the ill-fated Titanic.

|

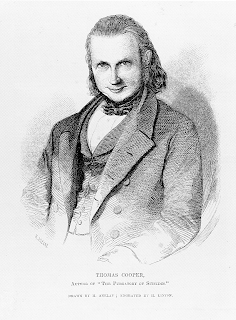

| Left Elizabeth Smith (standing) and her sister Sarah, right Commander E.J. Smith. Elizabeth's marriage to Mark Mason forged a link between the Mason and Spode dynasties and the captain of the Titanic. |

Elizabeth had two children before her marriage to Mark and there must be a serious doubt as to whether he was the father of Elizabeth’s first child, Ann, as he was only 16 years of age when she was born. Ann, was born on 28 July 1874 in the Union Workhouse, Chell (near Tunstall) and registered as ‘Ann Smith’ – no fathers name was provided. It looks as if Elizabeth’s family could not afford to provide for her and her child, or perhaps they threw her out because of what then, would have been a shameful event - their daughter having a child out of wedlock. How times have changed. On the 1881 census Ann, recorded as ‘Anne Smith Mason’, was living with her grandparents, George and Thirza Smith in May Bank, Wolstanton.

Elizabeth’s next child, Lydia Mason Smith, was born at May Bank on the 4 March 1877, seven weeks before her marriage to Mark. On the 1881 census she is staying at Goose Street, Newcastle under Lyme with her grandmother, Elizabeth Mason, widow of Charles Spode Mason.

Mark and Elizabeth’s third child, Florence Coyney Mason, was born on 26 March 1879 at Goose Street, Newcastle. She was undoubtedly named after Mark’s Aunt, Florence Elizabeth Coyney.

Two years later the family had travelled up to the north east of the country and on the 1881 census, Mark, (now calling himself James), his wife Elizabeth, and two-year old Florence were staying at a lodging house in Northowram, Yorks. Some of the occupants were described as cutlery grinders which has significance because the occupation on Mark’s death certificate was recorded as ‘scissor grinder’. Why did Mark decide to move away from the Potteries, leaving the two oldest children with the grandparents? Why call himself James? His Aunt, Elizabeth Spode, left him an inheritance to be paid on his twenty first birthday; was there some connection, or did he leave the area because of debts? You can but speculate.

Their next child, Elizabeth, was born at 2 Smith Street, Hartlepool, on the 1 September 1884. Elizabeth was the only child actually registered by Mark. The name and surname of the father is recorded as ‘James Spence Mason’ on the certificate. The name of the Registrar was Spence, so this may possible account for the discrepancy in Mark’s middle name.

Mark and Elizabeth’s last child, Charles Spode Mason - obviously named after his grand-father - was born on 25 April 1889 at 121 King Edward Street, Grimsby. The family had finally settled in Great Grimsby, Lincolnshire; a major fishing area.

‘At noon, on Friday, 20 February 1891, an inquest was held at the Great Coates Railway Station, before the District Coroner (Dr C. B. Moody) inquiring into the circumstances attending the death of James [Mark] Mason, 33 years of age, scissor grinder, late residing at Drakes Buildings, Grimsby. From the evidence produced it seems the deceased, who had been peculiar in his conduct for two or three days past, was observed walking along the Railway from Grimsby to Great Coates, on Thursday morning week. After standing somewhat irresolute on the line, he watched the morning express from Grimsby approach and deliberately flung himself in front of the Engine; the guard iron struck him on the head and turned him out of the way, and when assistance arrived some few minutes later he was found lying in a ditch beside the railway line. Life was then quite extinct.’

So reads the opening paragraphs of the report of the inquest. In her testimony, Mark’s wife Elizabeth told of the great difficulty they had experienced in maintaining the family of six since Christmas and how this had preyed on Mark’s mind. At the end of the proceedings, the jury, in an act of generosity, kindly devoted their fees to Elizabeth because of her straightened circumstances. There were no social services to fall back on, in those days.

It is only recently that the true circumstances of Mark’s death have been unearthed. Prior to this the family had always understood that Mark had been killed at a level-crossing on his way home – ‘drunk as usual’. No doubt the truth had been suppressed to avoid causing the children any undue distress.

Mark’s widow Elizabeth remarried the following year - with five children to bring up perhaps out of necessity. She married George William Johnson, a fisherman, on the 25 Dec. 1892 at St John’s Church, New Clee. By the time of the 1901 census, Elizabeth had two more children, a son, George Johnson, 8 years’ old, and a daughter, Gertrude Johnson, 5 years old. It was Gertrude who cared for her mother when she became old and infirm.

By the turn of the century, nearly all of Mark’s children had left home. Lydia had married John Cardy in 1896 and by the time of the 1901 census had borne three offspring; John, Florence Annie and George Hugh. It is possible more children followed.

Florence Coyney Mason married George Illingworth on the 1 January 1908, at the Church of St Peter in Bradford. They continued to live in the Bradford area and, as far as I know, they did not have any children.

Elizabeth married Swanson Carnes Trushell on the 26 August 1901 and had seven children over the next twenty years. Their eldest, Sidney Edward Trushell, is the father of Marjorie Burrett nee Trushell, who has provided me with a lot of information. Most, if not all, of the descendants of Elizabeth Mason and Swanson Trushell are known right up to the present time. They are too numerous to detail, but are illustrated on the accompanying family tree, although the most recent members of the family have been omitted to protect their anonymity. The eldest living descendant is Elizabeth’s daughter (Mark’s grand-daughter), Joyce Coyney Clarke nee Trushell.

Charles Spode Mason Junior, the youngest of Mark’s children, died of TB at the age of 36 years on 24 January 1926. He was employed as a Brewer’s cellar man and was staying at his mother’s house at the time of his death, so presumably he had not married.

We know very little of Elizabeth Smith’s first child Ann, except that she had a family and there are descendants living in America.

Acknowledgments: My special thanks to Marjorie Burrett, (a direct descendant of Miles Mason and Josiah Spode 1) and Lyane Kendall of New Zealand, a distant relative of the Mason family, for providing details of the Mark Spode Mason family tree. My own small contribution was to provide a little more detail on the individuals and to successfully trace the whereabouts of an inscribed pottery mug presented to Mark Spode Mason shortly after his fifteenth birthday. The mug in question was given to The Spode Museum Trust, Stoke in 1975 by a relative, to avoid any family dispute over ownership.

References: Birth, Marriage and Death certificates and Census Returns from the Family Record Centre London; The Grimsby News Fri. 20 Feb. 1891; extract of letter in the Haggar archives from the research notes of Peter Roden

Photo of Elizabeth and Sarah Smith courtesy of the late Marjorie Burrett.