|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

Florence was the youngest of four children born in late 1885 to coal miner Samuel Burton and his wife Harriet. Her father had died a few years after Florence’s birth and her mother had remarried, though by 1901, she was again a widow living at 3 Adam Place, Longton with her 18 year old son John Thomas Burton a potter’s presser, Florence who was a potter’s gilder, and an elderly boarder. The census was the last official document to record Florence alive, as the final act of a bizarre drama was playing out in the Burton family home.

For some time her mother Harriet had been getting increasingly worried about Florence, who had started drinking large amounts of vinegar and eating lemons. She had spoken to her daughter about it, but to no avail, the girl would scarcely eat anything without pickles or something else acidic. Florence’s friend Julia Brain later revealed that she knew that Florence had obtained large quantities of lemons from a local fruit shop ‘on trust’ and said that she had also seen her pour out a glass of vinegar, pour salt into it and drink it. When quizzed as to the reason for this Julia said it was to try and make her complexion ‘pale and nice’ giving her skin a translucent quality to make her more attractive; but in truth Florence’s beauty regime was gradually killing her. The end came suddenly in June 1901 when Florence was at work and suffered chest pains that made her so ill that she had to go back home. Once there she reportedly suffered a fit and died shortly afterwards.

As a result of her sudden death, a post-mortem was carried out by a Dr Howells, who reported to the inquest into the girl’s death that Florence had died due to heart disease caused by her unusual diet. Her practice of consuming large amounts of vinegar, salt and lemons would, he said, ‘disorganise the whole system, upset digestion and cause the person to be half-starved, though well and apparently well nourished.’

The Coroner, clearly flabbergasted by what he had heard, asked the surgeon, “Why do girls do these things?” Dr Howells answered, “To make them pale and interesting-looking. They like to look transparent.” - “And it kills them?” - “It does.” The Coroner commented on the folly of such practices and the jury returned a verdict of ‘Death from Natural Causes.’

Reference: Birmingham Mail, 28 June 1901, p.4; Coventry Evening Telegraph 28 June 1901, p.2.)

Being situated in such a hilly region, widespread flooding is a rarity in Stoke-on-Trent, but occasionally chance extremes of weather have briefly put parts of the area under water. One startling weather event occurred on the afternoon of Sunday, 7 July 1872, when what the Staffordshire Advertiser described as 'a thunderstorm of great severity', struck the Potteries. Though it only lasted an hour and a half, it was so fierce that it left in its wake many dozens of flooded or damaged properties and a somewhat shell-shocked populace. Considering the violence of the storm and the damage it caused, remarkably few people were injured, though it seems there were many close calls.

It had been cloudy all day, but in the afternoon the sky began to grow much darker presaging a storm, the light becoming so dim that newspapers could only be read near to windows or by candle or gas light. The dark clouds then gave way to ones with a strange yellow tint to them and it was then that it started to rain, not in drops, but as a veritable deluge driven in by a fierce wind and accompanied by loud claps of thunder and multiple bolts of lightning. In Hanley there was one very alarming event when a bolt of lightning passed through the Primitive Methodist school room in Frederick Street (now Gitana Street), entering by one window and out through another. The only damage was a scorched paint board on the front of the building, but the room had been full of children when the lightning shot through and these now fled the room in panic. They had to descend a flight of stairs to get out of the building and while none had been injured by the lightning, several now fell and were trampled underfoot and bruised in the crush, though none of them seriously.

During a service at Shelton Church, it rained so heavily that water forced its way through the roof and poured down into the building in streams. Buckets had to be brought to catch the water and the noise produced during the saying of the litany is said to have made for a very curious sound. Elsewhere in town, the lobbies of Bethesda Chapel in Old Hall Street were flooded, so too were numerous houses in town, notably in Nelson Place where part of the road nearby carrying a tramway was washed away. In Hanover Street, the downpour lifted stones up out of the road and deposited them at the bottom of Hope Street, where a heap big enough to fill two barrows was collected. The bottom end of Hope Street itself flooded, filling the cellars with up to a foot of water, floating heavy beer barrels in a brewery and boxes of live chickens in one house. The damage done to yards and gardens was tremendous. Nor were the local pot banks immune. The Cauldon Place works were flooded, though no serious damage was caused. Hanley's satellite villages were likewise hard hit. At Basford a lightning bolt shot down a chimney and blew away a portion of a mantle shelf in one of the rooms; Etruria saw dozens of properties flooded, as too did Bucknall, where the water rushing down the roads and through the houses quickly threw the Trent into spate, causing it to overflow. This caused enormous damage on the low-lying ground of the neighbouring Finney Gardens where Bucknall Park now stands, some of the walks, plants and flowers being washed away by the sudden inundation.

Probably in no other part of the Potteries were the effects the storm so severe than in Burslem. Reporters on the scene shortly afterwards noted that even the oldest inhabitants had never before witnessed such a tempest, one stating that the rain 'came down in bucketfuls'. The rain here was particularly heavy and for more than an hour the thunder and lightning was incessant and at one point the wind rose to a terrible pitch causing major damage in several places. On the Recreation Ground (where the old Queens Theatre now stands), Snape's Theatre, a temporary structure of wood and canvas which had been constructed for the town's wakes week, was in a matter of minutes blasted to smithereens. A number of the thickest supports were splintered like matchwood and many of the rafters and seats were destroyed, while the canvas roof was torn to shreds as the wind hit it. Mr Snape was a veteran travelling showman, well liked in the district and there was a great deal of local sympathy for him over his losses. In the aftermath of the storm a fund was set up, subscriptions to which would hopefully help him in repairing the serious losses he had sustained.

|

| The Big House, Burslem. |

At the Roebuck Inn in Wedgwood Place, the violence of the rainstorm split some of the roof tiles, causing a mass of water to cascade into the upper rooms, then down the stairs and out through the front doors. The Town Hall too received a soaking, the basement of which was flooded to a depth of three feet, which caused no end of problems for the hall keeper and his wife who had the job of clearing it all out. Likewise the row of houses in Martin's Hole – literally a hole or hollow near the Newcastle Road, where the roofs of the houses were on a level with the road – 'presented a truly pitiable appearance', the buildings being flooded to a depth of four and a half feet, ruining food stores and furniture and forcing the luckless inhabitants to seek shelter on the upper floor.

Almost everywhere else it was the same story with only slight variations. Longport received a severe visitation with most of the houses flooded to several feet. At Middleport the canal overflowed adding to the chaos. At Tunstall, water poured into the police station and several houses doing much damage. In Smallthorne numerous houses were flooded and smaller items of furniture were flushed out of the doors and sent floating down the street. At Dresden as well as the numerous flooded properties, the road at the lower end of the village was split apart by the storm, leaving it looking for all the world as if it had been heavily ploughed, which made it impassable to traffic and men had to be brought in to make repairs. In Stoke, Fenton and Dresden as in Burslem, many householders were forced briefly to live upstairs as their ground floors filled up, sometimes as high as the ceiling. Longton too suffered torrential rain and likewise had some flooding, but saw much less material damage, though at one pot bank the downpour extinguished the fires in their kilns.

Then the storm passed, leaving the Potteries in a battered state that it would take several days to recover from. That evening another storm broke overhead, but this turned out to be a much less severe event and caused no more serious problems.

Reference: Birmingham Daily Post, Tuesday 9 July 1872, p.5; Staffordshire Advertiser, Saturday 13 July 1872, p.5.

Regular newspaper coverage of events in the Potteries only really started at the end of the 18th century with the advent in 1795 of the Staffordshire Advertiser paper, though as this was published in Stafford, it's coverage of the goings on in the north of the county was limited to the most noteworthy events. Another half century would pass before more local newspapers were being produced in Hanley, Stoke and Burslem. However, histories, travellers journals and some other national or regional papers occasionally carried tales from the Potteries from this early period giving us fleeting glimpses into life in the area.

* * * * *

The next day Wesley preached a second sermon in Burslem to twice the number of the day before. 'Some of these seemed quite innocent of thought. Five or six were laughing and talking till I had near done; and one of them threw a clod of earth, which struck me on the side of the head. But it neither disturbed me nor the congregation.'

(John Wesley, Journal, 8-9th March 1760)

P. S. I have just seen a Hen, which laid Twelve Eggs only, from which she has brought up Twelve Cock Chickens, which is looked upon as somewhat remarkable.'

(Extract of a Letter from Burslem,14 August 1766, Derby Mercury, Friday 29 August 1766, p.2)

'Yesterday we took a walk to the famous subterraneous canal at Harecastle, which is now opened for a mile on one side of the hill, and more than half a mile on the other, of course the whole must be compleated in a short time. As it is not yet filled with water, we entered into it, one of the party repeating the beautiful lines in Virgil, which describe the descent of Æneas into the Elysian fields. On a sudden our ears were struck with the most melodious sounds. - Lest you should imagine us to have heard the genius or goddess of the mountain singing the praises of engineer Brindly, it may be necessary to inform you, that one of the company had advanced some hundred paces before, and there favoured us with some excellent airs on the German flute. You can scarcely conceive the charming effect of this music echoed and re-echoed along a cavern near two thousand yards in length.'

(Leeds Intelligencer, Tuesday 14 July 1772, p.3)

A month later, in an issue of the Staffordshire Advertiser that noted that thermometers in Macclesfield had measured temperatures as low as -21° F (-29.4° C), the fearsome nature of the winter was highlighted dramatically by one small but rather macabre snippet of news. 'Through the inclemency of the night of Saturday last [i.e.,14 March] a poor man perished betwixt Hanley and Bucknall. He unfortunately lost himself in attempting to cross the fields, and was found on Sunday standing upright in a snow drift, with his hand only above the surface.'

(Staffordshire Advertiser, 7 February 1795, p.3; 21 March 1795, p.3.)

(Staffordshire Advertiser, Saturday, 6 April 1799, p.4)

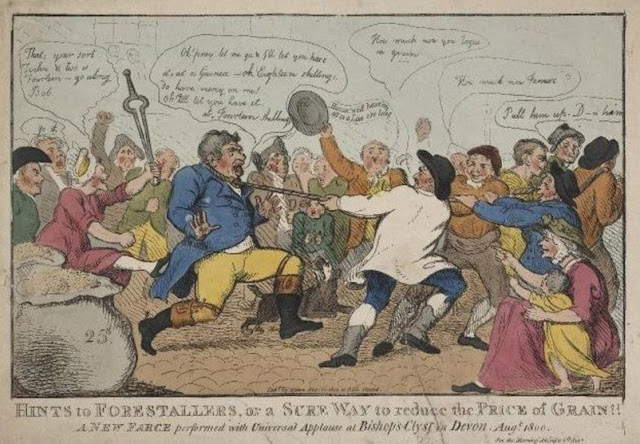

Between 1799 and 1801 food riots, brought on by scarcity and high prices which in turn had been caused by poor harvests and the effects of Napoleon’s continental blockade, regularly broke out throughout England. With imports being limited, grain was at a premium which increased the price of bread, the cost of a loaf jumping to an all time high of 1s.9d, while other foods such as butter and cheese saw similar hefty hikes in price, a situation not helped by greedy profiteers inflating prices further still. As many of the poor working classes lived off a diet in which bread and other basics played a major part, any serious increase in their prices was bound to cause problems and spark often violent protests. London, Birmingham, Oxford, Nottingham, Coventry, Norwich, Stamford, Portsmouth, Sheffield and Worcester, amongst other places all saw bouts of rioting at this time and the Potteries too suffered several outbreaks.

|

| A satirical cartoon depicting a fat 'forestaller' being dragged along by a rope round his neck by a chain of countrymen, to the cheers of a crowd. Illustration by Isaac Cruikshank |

On Monday 28 April 1800, a serious food riot broke out after a mob assembled at Lane End and seized a quantity of potatoes, flour and other goods, which they quickly shared out among themselves. The rioting became so serious and alarming that the local Volunteers were called out and the Riot Act was read, though to little effect. So the authorities had to get tough and the Volunteers were sent to capture the ringleaders and after a scuffle seven people were dragged off to Stafford gaol guarded by a party of the Newcastle and Pottery troop of Cavalry. They were William Hatton, William Doukin (or Dowkin), William Myatt, Solomon Harding, Emma Vernon, Ann Goodwin and Sarah Hobson, all of whom were subsequently sent for trial at the Stafford Assize in August. Most were acquitted, but 29 year old Emma Vernon also known as Emma Berks or Amy Burke, who was identified as the chief troublemaker, was found guilty of riotous assembly 'with other persons above the number twelve, and continuing together for one hour after Proclaimation'.

At the time rioting was a capital offence and Emma was initially sentenced to be hanged on 30 August at Stafford, but on 13 August her sentence was commuted to one of transportation for 21 years to Australia. In June 1801, Emma Berks (alias Emma Vernon, Amy Burke) was one of 297 prisoners transported aboard the curiously named ship Nile, Canada and Minorca, which arrived in New South Wales on 14 December 1801. She would never return, dying in Australia on 1 July 1818, aged 47.

The April riot, though, was not the last to plague the area and in late September more trouble broke out. The Staffordshire Advertiser, whilst praising the exemplary fortitude of the locals during the ongoing food crisis, was dismayed to report 'that since Monday last [22 September] a disposition to riot has manifested itself in various parts of the Potteries.' Miners and potters were reported to have assembled in large groups and going to local food shops had seized provisions and sold them on at what they considered fairer prices. A troop of the 17th Light Dragoons quartered at Lane End, the Trentham, Pottery and Stone Troops of Yeomanry Cavalry, plus the Newcastle and Pottery Volunteers had been repeatedly called out to deal with these infractions and thus far had managed to keep a lid on the situation, curbing any dangerous acts by the mobs. Indeed, the only overtly violent act that the Advertiser could report was that one boy had been seized for hurling stones and was taken into custody. More pleasingly it was noted that some the inhabitants of Hanley and Shelton in an effort to stamp out the blatant profiteering at the root of the troubles, had made a collective resolution not to buy butter from anyone selling at more than 1 shilling per lb and various communities around the Potteries were following suit. Prior to this butter had been shamefully priced at 16d or 17d per lb. The Marquis of Stafford also stepped in and ordered his tenants to thresh their wheat and take it to market, which many did, selling it at the reasonable price of 12s per strike [i.e. 2 bushels]. The paper lauded such actions and hoped that it would promote further reductions in prices. Certainly it quelled the growing unrest in the area and by the the next edition of the paper the Potteries had returned to 'a state of perfect tranquillity', with 'the pleasing prospect of the necessaries of life being much reduced in price.'

(Staffordshire Advertiser, 3 May 1800, p.4; 23 August 1800, p.4; 30 August 1800, p.4; 27 September 1800, p.4; 4 October 1800, p.4)

|

| Napoleon Bonaparte Author's collection |

|

| L to R: Dolly Shepherd and Louie May |

|

A wildly exaggerated newspaper illustration of the

incident. Not only are details of the rescue incorrect

but in reality Dolly and Louie's knickerbocker

suits were much more practical.

|

|

| Newcastle's impressive Russia cannon in situ. The carriage was mass-produced at the Royal Armouries in Woolwich. |

|

| Thomas Cooper addresses the crowd at Crown Bank, Hanley. AI recreation of the scene after a drawing by the author. |