|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

|

| A Royal Marine private in 1815 Source: Wikimedia Commons |

The account had no doubt that Mottershead had ‘been in many a scrimmage’ from early in his career at sea, but Trafalgar would overshadow them all. By 1805, he was a serving Marine aboard HMS Dreadnought, a 98 gun second-rate ship under Captain Conn, part of Nelson’s force in full pursuit of Admiral Villeneuve’s Franco-Spanish fleet. Mottershead recalled how, ‘… when the combined fleets of France and Spain were signalled a great shout went up. On that day he [Mottershead] had nothing on but his shirt and trousers and said that he and seven others made a hasty breakfast out of one dish. Owing to the line of battle taken up by the fleet the Dreadnought was late in coming into action and so was not so hotly engaged as some of the ships, but, nevertheless, they captured one of the Spanish vessels.’

This was the San Juan Nepomuceno, whose fire-eating captain had nailed the ship’s colours to the mast and refused to surrender, despite taking a pummelling from half a dozen circling British warships. As already noted Dreadnought joined the fray late and opened fire at two o'clock then fifteen minutes later boarded the Spaniard and forced her crew to surrender after their captain had been killed in action. Dreadnought then turned in pursuit of the Spanish flagship Principe de Asturias, firing several broadsides and mortally wounding the Spanish Admiral Gravina, but was unable to catch the enemy vessel which slipped away and succeeded in reaching Cadiz. Captain Conn consoled himself with his initial prize, the San Juan Nepomuceno being one of only four captured enemy ships to survive the great storm that followed on after the battle.

HMS Dreadnought suffered 7 crew killed and 26 wounded in the fighting, but Mottershead was lucky and seems to have come away unscathed. Not that his family back in Leek were to know that and when a Mr Beadnall was passing the Mottershead’s home near Belle Vue, he spotted Joe’s sister and asked her what ship her brother was serving on. On being told it was the Dreadnought, he informed her that the ship had been in a great sea battle and the British fleet had won. The news drove the family frantic with worry, wondering if Joe had been killed and it was not until several weeks later when they received a letter from him stating that he was safe and well, that their fears were finally allayed.

Mottershead’s account of his career added a few more details of his time at sea. He had stated that his ship was once ice-bound for a long period and the men were put on short rations. When they finally got free and returned to Portsmouth, Mottershead said ‘they could almost see through each other’. He also recalled that he once saw a group of his comrades hung from the yardarm for breach of their duty. When these incidents happened, though, is not made clear.

Joseph Mottershead was discharged from the Royal Marines in either 1814 or 1815. Servicemen of the period were usually provided with the fare back to the town where they had enlisted, but otherwise had to make their own arrangements to get back to their real home. His low-key return to Leek was recounted in Miller’s book.

‘One very wintery day about the year 1815, Gaunt’s work people had been paid for their work and were getting “a glass together” at the Cock in Derby street, when the coach from Derby drew up and a soldier got off and came into the house. He stood by the fire warming himself, and presently he asked “Is ------ alive,” naming his father. One of the people, a woman of the name of Nixon, eyed him for a moment, then rapping her snuff-box and turning to one of the men (Mottershead’s brother) said, “By Jove, Will, it’s your Joe!” Yes! Joseph was come back and received a hearty welcome.’

|

| A replica Naval General Service Medal with the Trafalgar clasp. |

Joseph Mottershead, North Staffordshire’s most notable Trafalgar veteran died on 4 December 1855 aged 77 years old and was buried four days later in St Edward’s Churchyard. His death and claim to fame was mentioned briefly in the pages of the Staffordshire Sentinel, where it was noted, ‘He fought by the side of Nelson, at the Battle [of] Trafalgar.’

Reference: M. H. Miller, Leek: Fifty Years Ago, pp.150-151. Staffordshire Sentinel, 8 December 1855, p.5.

(Cor. Boston Traveller)

'For the truth of the incident related below I have the most possible proof: George Shaw, a brave Englishman, when surrounded on the field at Waterloo by a number of the enemy, made a gallant struggle for existence, and fought his way back to his comrades over the dead bodies of a dozen Frenchmen whom he had slain. As a reward for his bravery, Wellington sent for the soldier, and in the course of his conversation with him, gave him permission to take home with him whatever relic he chose from the battlefield. Shaw's choice was the skeleton of a French General, killed in the action. The ghastly trophy was safely transported to England and hung in the soldier's closet at Hanley and Staffordshire, England, till he came to regard it is a nuisance and disposed of it to Samuel Bullock, a manufacturer of china. As bones form a large proportion of the ingredients from which English china is made, it occurred to the manufacturer that the remains of the poor General would look much better made up in some handsome ornament than dangling from a peg in an obscure closet; and in accordance with this inspiration, the French General was ground down, and, in due time, was metamorphosed into teacups and saucers; in which condition he adorns to this day the museum at Hawley, appropriately inscribed with the history of his transformation. It happened one day that Marshal Soult visited the museum, and his attention was attracted by the china, which has a bright pink tint and is ornamented with flowers. But when his eye rested upon the label, which enabled him to recognize in the collection the remains of one of his former generals, the marshal was deeply shocked; and, "wrapping his martial cloak around him," walked indignantly away. He did not forget to inform Napoleon, then at St. Helena, of the indignity which had been offered to the memory of their departed countryman. "It is no indignity," quoth Napoleon; "what more pleasing disposition can there be of one's bones after death than to be made into cups to be constantly in use; and placed between the rosy lips of ladies? The thought is delightful!" This was an aspect of the case which had net occurred to the prosaic marshal; but he was forced to content himself with it.'

The story seems to be a bare-faced mix of fact and fantasy the exploits of 'George Shaw' mimicking somewhat the story of Corporal John Shaw, a noted pugilist and artists' model who served with the Life Guards at Waterloo, where he was killed fighting several French cavalrymen.

Reference: numerous US newspapers, see for instance The Somerset Press (Somerset, Ohio) 11 December 1879, p.1

|

| 'The Battle of Trafalgar' by William Clarkson Stanfield Source: Wikimedia Commons |

On 21 October 1805, a British fleet of 27 ships commanded by Admiral Horatio Nelson caught up with and attacked a combined Franco-Spanish fleet of 33 ships off Cape Trafalgar between Cadiz and the Strait of Gibraltar. In the battle that followed, Nelson was mortally wounded by a sharpshooter, but before he died he heard the news that his fleet had inflicted a devastating defeat on the enemy force, capturing 20 ships, thus ending for good any lingering threat of a French invasion of Britain. It was also a victory that established British naval dominance for the next century.

Admiralty records held at The National Archives in Kew, clearly show that despite hailing from so landlocked a region several men from the Potteries were involved in this decisive sea battle. Two of them served together aboard Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory.

Corporal William Taft, Royal Marines, HMS Victory

Depending on which of his records you believe, William Taft, was born in Hanley Green (present-day Hanley town centre) in either 1775 or 1777, though the earlier date seems the most likely. There is no trace of his birth or of his parents locally, though their records like many others may have been lost when the registers of St John’s church in Hanley were destroyed in the Pottery Riots in 1842. Army and Royal Marine records, though, make up the deficit somewhat and through them we learn that William was the son of Ralph and Hannah Taft. In his teens he worked briefly as a potter, before he enlisted in the army in early 1793, joining the 11th Light Dragoons. He served with that regiment for just over two years before transferring to the 27th Light Dragoons on 25 April 1795. Records show that he was a smallish man being only 5’ 4¼” tall, (he was listed as 5’ 5” as a Royal Marine) with a fresh complexion, dark brown hair and brown eyes and the fact that he always signed with his mark reveals that like many common soldiers he was illiterate. Military life seemed to agree with him, though, and Taft remained with the 27th Light Dragoons until 20 October 1801, when for reasons unspecified he was invalided out of the service.

For a time Taft found employment as a labourer, but was soon drawn back to military service, though not this time in the army, enlisting instead in the Royal Marines at Rochester (probably the town in Kent) on 13 April 1803, where he joined Nº16 Company of the Chatham Division. Four days later Private Taft was posted as part of the marine detachment aboard HMS Victory. This big three decker first-rate ship of the line had just undergone an expensive reconstruction at Chatham dockyard and with its new crew on board in May it set sail for Portsmouth. Once there, the ship was joined by Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson who chose Victory as his flagship.

The ship was in the Mediterranean when on 5 March 1805, William Taft was raised to corporal and he served in that capacity during Nelson’s dash across the Atlantic in pursuit of the Franco-Spanish fleet and later at Trafalgar. As the lead ship of the weather division, Victory was in the thick of the action from the beginning of the battle, crippling the French ship Bucentaure with it’s first broadside before becoming involved in a protracted fight with another French ship Redoutable and the ship’s company suffered many casualties as a result, most notably Admiral Nelson, who was shot by a French marksman and taken below where he subsequently died. Corporal Taft was another of the injured, badly wounded in the upper left arm during the fighting; his shattered limb could not be saved and was amputated at the neck of the humerus (i.e., just below the shoulder ball joint). Surviving the fight, the amputation and a violent storm that nearly wrecked the battered warships after the battle, Taft was admitted to the hospital in Gibraltar on 29 October 1805, being formally dismissed from Victory’s crew on 4 November 1805. On 10 January 1806, Taft was transferred to the hospital ship Sussex for transport home and just over a month later on 11 February and presumably back in Britain, he was discharged at headquarters. Only three other documents list his progress after that; on 3 March he was dismissed from the Royal Marines as an invalid and the next day he received a pension of £8. Then on 7 April in the Rough Entry Book for Pensioners we learn that he was a married man and was lodging at the Wheat Sheaf, Market Place, Greenwich. His fate after that is unknown.

Like all the surviving sailors and Marines who fought at Trafalgar, William Taft was also awarded prize money of £1 17s 8d and granted a Parliamentary award of £4 12s 6d. Presumably because of his career-ending injury, Taft also received £40 from the Lloyds Patriotic Fund.

Private William Bagley, Royal Marines, HMS Victory

William Bagley was born in Stoke in about 1774, though nothing is known about his parents, nor much about his early years, though at some point prior to serving in the Royal Marines he spent 4 years and six months as a soldier in the 4th Dragoons. He seems to have been married, certainly he had a daughter named Susannah who later lived in Hanley, but there are no local records of who William’s wife was, nor of Susannah, these again may have been victims of the records burnt in the riots in 1842. After his army service William may have returned to the Potteries as he was listed as having worked as a potter prior to joining the Royal Marines.

He enlisted in the Royal Marines on the same day as William Taft, 13 April 1803, and although Bagley was posted to Company 7 of the Chatham Division there seems to have been a connection between the two men, perhaps they were friends. It is notable too that after Bagley and William Taft were both posted to HMS Victory on 17 April, they were always listed together, Bagley and then Taft, in the ship’s muster roll. On his enlistment William Bagley was described as being 5’ 10” tall, with dark hair and a fresh complexion.

Unlike Taft, Bagley was never promoted, but he was much luckier during the battle of Trafalgar and survived the encounter uninjured. After the battle Victory was towed to Gibraltar for repairs before returning to Britain in December 1805. Bagley was discharged from the ship on 17 January 1806 at Chatham, but on 26 January he suffered a serious fall at headquarters and died from his injuries. He did not collect his prize money from the battle which was donated to the Greenwich hospital, while his personal effects were returned to his daughter Susannah in Hanley.

Private Richard Beckett, Royal Marines, HMS Royal Sovereign

Private Richard Beckett was a 24 year old from Burslem, 5’ 6” tall with light hair a fair complexion and grey eyes and prior to enlisting had worked locally as a potter. He had enlisted in the Royal Marines at Stafford on 2 May 1803 and served for 7 months with the Chatham Division before being moved to the Portsmouth Division where on 31 August 1805 he was posted as part of the Royal Marine detachment aboard HMS Royal Sovereign. Like Victory, this ship was a first-rate three decker and at Trafalgar she served as the flagship of Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, the second-in-command of the fleet. The ship had recently had her keel re-coppered and as a result she was a very fast sailer, a fact which showed as she led the lee squadron of the fleet into battle, racing ahead of the other British ships and being the first to break the enemy line.

For most of the battle Royal Sovereign fought with a Spanish ship the Santa Ana. Both vessels suffered heavy casualties before the Santa Ana surrendered, but Private Beckett was uninjured. Like everyone in the fleet he was entitled to prize money, £1 17s 8d in his case, but did not collect it and the money was instead donated to the Greenwich hospital. He did, though pick up the Parliamentary award of £4 12s 6d given to men of his rank. He was illiterate and signed his mark.

Private Joseph Sergeant, Royal Marines, HMS Prince

Joseph Sergeant was born in Clayton in about 1775 or 1776. He worked briefly as a glazier, but on 10 January 1798 at Kidderminster he enlisted in the Royal Marines. On his enlistment he was described as 5’ 5” tall with brown hair and a fresh complexion. A member of Company 37 of the Chatham Division on 22 December 1803, Sergeant joined the marine contingent aboard HMS Prince a second-rate ship of the line attached to the Channel Fleet which by October 1805 was part of Nelson’s fleet set to engage the Franco-Spanish fleet at Trafalgar. A slow ship, Prince was passed by most of her division as they sailed into battle and by the time the ship arrived at the fighting the battle was nearly over, though opening fire on a couple of enemy ships Prince managed to set fire to and de-mast the French ship Achille. Prince launched boats to rescue Achille’s crew and managed this before the ship exploded. HMS Prince suffered no damage and took no casualties and proved herself a real godsend in the week of storms that followed the battle, rescuing numerous crews from sinking ships and transporting then safely to Gibraltar before going back for more.

Sergeant received his share of the prize money of £1 17s 8d from the battle but did not collect the healtheier parliamentary award and the money went to the Greenwich hospital. He stayed aboard HMS Prince and just over a year later on 12 November 1806, he was promoted to the rank of corporal of 58 Company. On 20 December 1808 he was promoted once more to sergeant of 55 Company. He remained in the Royal Marines until he was disbanded from the service on 13 September 1814. What happened to him after that, though, is unknown.

John Bitts, Landsman, HMS Naiad

John Bitts claimed to have been born in Stoke, Staffordshire, but as with many of the other men here nothing is known of his background or family, no local records mention him. He was aged 24 at the time of the battle of Trafalgar which puts his date of birth in 1781 or 1780. He seems to have been illiterate, signing with his mark and no indication is given as to how he had ended up in the navy, save that he joined the crew of the Naiad on 17 March 1803 as a volunteer. His ship was part of Nelson’s fleet at Trafalgar, but being a small frigate Naiad kept out of the fighting between the bigger ships, though she was involved in the mopping up after the fighting ended. He escaped the battle uninjured and unlike many Bitts claimed both the prize money of £1 17s 8d and the Parliamentary award of £4 12s 6d. Nothing is known of his life and career after Trafalgar.

John Williams, Carpenter’s Crew, HMS Leviathan

According to his navy records, John Williams was born in Stoke, Staffordshire, in about 1778, but nothing more is known about his early life. The records state that he had been pressed into the navy and that prior to joining the Leviathan on 24 February 1803, he had served aboard the frigate HMS Pegasus in the Mediterranean. As part of the carpenter’s crew, Williams would have worked to keep the ship in a good seaworthy condition. The Leviathan was a 74 gun third rate ship of the line and at Trafalgar was one of the ships of the weather squadron that followed HMS Victory into battle, where she captured a Spanish vessel. Williams got through the battle uninjured and later received prize money of £1 17s 8d.

Reference: The National Archives, ADM 44 Dead Seamen's Effects; ADM 73 Rough Entry Book of Pensioners; ADM 82 Chatham Chest: ADM 102.

Ken Ray, a long-time researcher into the lives of local soldiers has assembled an impressive list of North Staffordshire men who served in the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimea and the numerous colonial conflicts Britain participated in during the 19th and early 20th centuries. He has very kindly given me access to some of his documents which chart the lives and careers of ordinary men from the region who might otherwise have been forgotten. This is one of those stories...

. . . .

Private Philip Yates, Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (Oxford Blues)

Napoleonic Wars

|

| The Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards (foreground) at Waterloo |

After Waterloo and Napoleon's abdication, the Royal Horse Guards remained in France until 1816, when they returned to their base at Windsor and the rest of Private Yates' service was at home. On his discharge from the army on 5th February 1827, Yates was described as being 43 years old, 5' 10½” tall, with brown hair, grey eyes and a fresh complexion; his conduct as a soldier had been good. The reason for his discharge was due to length of service and amounted to 22 years and 43 days with the Colours, plus the 2 extra years service granted to all Waterloo veterans.

Yates returned to the Potteries after his discharge, travelling from Windsor to Hanley Green, where he picked up the threads of his old life, helped on by a Chelsea pension. Five years later on 24th June 1832, he married widow Elizabeth Pope (possibly nee Orton) in Hanley. In 1841 they were living in Brunswick Street, Shelton. Philip was back working as a glazier, Elizabeth's trade is hard to read as too is that of her 15 year old son from her previous marriage, John Pope, though he may have been a pottery packer; the fourth member of the household was Philip and Elizabeth's eight year old daughter Elizabeth. On a personal note, when I looked at the 1841 census entry, I was surprised and pleased to discover that Philip Yates and his family lived only two doors away from my great, great, great grandparents Thomas and Ann Cooper and their family.

One Philip Yates died in 1847 aged 66 and was buried on 26th December 1847. He had lived long enough to apply for the Military General Service Medal, as it was awarded with the two clasps for his Peninsula War service.

Reference: UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949, Battle of Waterloo 1815, p.23; UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949: Napoleonic Wars 1793-1815, p.193; UK, Waterloo Medal Roll, 1815; UK, Royal Hospital, Chelsea: Regimental Registers of Pensioners, 1713-1882, p.58; WO97 Royal Hospital Chelsea: Soldiers' Service Documents;1841 census for Shelton, Stoke-on-Trent.

Between 1799 and 1801 food riots, brought on by scarcity and high prices which in turn had been caused by poor harvests and the effects of Napoleon’s continental blockade, regularly broke out throughout England. With imports being limited, grain was at a premium which increased the price of bread, the cost of a loaf jumping to an all time high of 1s.9d, while other foods such as butter and cheese saw similar hefty hikes in price, a situation not helped by greedy profiteers inflating prices further still. As many of the poor working classes lived off a diet in which bread and other basics played a major part, any serious increase in their prices was bound to cause problems and spark often violent protests. London, Birmingham, Oxford, Nottingham, Coventry, Norwich, Stamford, Portsmouth, Sheffield and Worcester, amongst other places all saw bouts of rioting at this time and the Potteries too suffered several outbreaks.

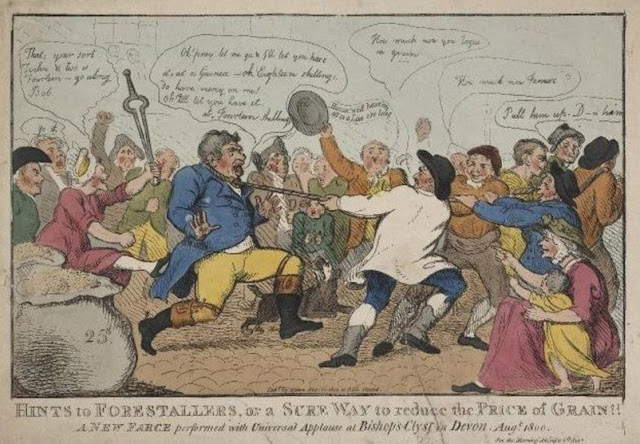

|

| A satirical cartoon depicting a fat 'forestaller' being dragged along by a rope round his neck by a chain of countrymen, to the cheers of a crowd. Illustration by Isaac Cruikshank |

On Monday 28 April 1800, a serious food riot broke out after a mob assembled at Lane End and seized a quantity of potatoes, flour and other goods, which they quickly shared out among themselves. The rioting became so serious and alarming that the local Volunteers were called out and the Riot Act was read, though to little effect. So the authorities had to get tough and the Volunteers were sent to capture the ringleaders and after a scuffle seven people were dragged off to Stafford gaol guarded by a party of the Newcastle and Pottery troop of Cavalry. They were William Hatton, William Doukin (or Dowkin), William Myatt, Solomon Harding, Emma Vernon, Ann Goodwin and Sarah Hobson, all of whom were subsequently sent for trial at the Stafford Assize in August. Most were acquitted, but 29 year old Emma Vernon also known as Emma Berks or Amy Burke, who was identified as the chief troublemaker, was found guilty of riotous assembly 'with other persons above the number twelve, and continuing together for one hour after Proclaimation'.

At the time rioting was a capital offence and Emma was initially sentenced to be hanged on 30 August at Stafford, but on 13 August her sentence was commuted to one of transportation for 21 years to Australia. In June 1801, Emma Berks (alias Emma Vernon, Amy Burke) was one of 297 prisoners transported aboard the curiously named ship Nile, Canada and Minorca, which arrived in New South Wales on 14 December 1801. She would never return, dying in Australia on 1 July 1818, aged 47.

The April riot, though, was not the last to plague the area and in late September more trouble broke out. The Staffordshire Advertiser, whilst praising the exemplary fortitude of the locals during the ongoing food crisis, was dismayed to report 'that since Monday last [22 September] a disposition to riot has manifested itself in various parts of the Potteries.' Miners and potters were reported to have assembled in large groups and going to local food shops had seized provisions and sold them on at what they considered fairer prices. A troop of the 17th Light Dragoons quartered at Lane End, the Trentham, Pottery and Stone Troops of Yeomanry Cavalry, plus the Newcastle and Pottery Volunteers had been repeatedly called out to deal with these infractions and thus far had managed to keep a lid on the situation, curbing any dangerous acts by the mobs. Indeed, the only overtly violent act that the Advertiser could report was that one boy had been seized for hurling stones and was taken into custody. More pleasingly it was noted that some the inhabitants of Hanley and Shelton in an effort to stamp out the blatant profiteering at the root of the troubles, had made a collective resolution not to buy butter from anyone selling at more than 1 shilling per lb and various communities around the Potteries were following suit. Prior to this butter had been shamefully priced at 16d or 17d per lb. The Marquis of Stafford also stepped in and ordered his tenants to thresh their wheat and take it to market, which many did, selling it at the reasonable price of 12s per strike [i.e. 2 bushels]. The paper lauded such actions and hoped that it would promote further reductions in prices. Certainly it quelled the growing unrest in the area and by the the next edition of the paper the Potteries had returned to 'a state of perfect tranquillity', with 'the pleasing prospect of the necessaries of life being much reduced in price.'

(Staffordshire Advertiser, 3 May 1800, p.4; 23 August 1800, p.4; 30 August 1800, p.4; 27 September 1800, p.4; 4 October 1800, p.4)

|

| Napoleon Bonaparte Author's collection |

|

| The uniform of the 4th Kings Own Regiment from 1799 to 1809, after which the breeches and stockings were replaced with grey trousers. |

|

| The final attack on Badajoz, showing British troops assailing the walls with ladders |

|

| The uniform of the 1st Regiment of Foot (Royal Scots) at the time of the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. |