|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

|

| French cuirassiers charge a British square at Waterloo, painting by Felix Philippoteaux. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

|

| Present day Hougoumont Author's collection. |

|

| A RHA Troop under attack. |

|

| Richard Caton Woodville's famous painting of the Charge of the Light Brigade. Lord Cardigan on the far left of picture is dressed as the commander of the 11th Hussars. Source: Wikimedia Commons |

In 1975, a small article appeared in the Evening Sentinel noting that at the battle of Balaclava during the Crimean War, 1358 Private George Turner* of the 11th Hussars, born in Burslem, had been mortally wounded during the Charge of the Light Brigade. According to his records, Turner was indeed from Burslem, and had worked locally as a crate maker until at the age of 18 he had enlisted in the 11th Hussars at Coventry on 24 September 1847. As the paper noted, he was probably the only man from the Potteries to have taken part in that famous but suicidal military action, when on 25 October 1854, a force of nearly 670 light cavalrymen were mistakenly launched in a frontal attack on an extended line of Russian cannon, infantry and cavalry at the end of a valley, that were further supported by other batteries on either side. The results of this colossal blunder were predictable, with some 110 British soldiers being killed and 160 wounded in the attack, a 40 percent casualty rate, while over 300 horses were killed.

The 11th Hussars, resplendent in their black fur shakos, blue and gold braided jackets and crimson trousers, formed half of the second rank of the Light Brigade, though that did not spare them and they took a severe mauling from the Russian cannons as the Brigade closed on the enemy line. Private Turner was one of those struck down well before they got there, hit on the left arm by a cannonball, his injury being witnessed by Sergeant Major George Loy Smith of his company, who was riding nearby. Loy Smith later wrote ‘… before we had gone many hundred yards Private Turner’s arm was struck off close to the shoulder and Private Ward was struck full in the chest.’ Another Private named Young had received a similar injury to Turner and Loy Smith told him to turn his horse around and go back to their own lines, ‘… I had hardly done speaking to him, when Private Turner fell back, calling out to me for help. I told him too, to go back to the rear.’

The rest of the brigade rode on down the valley and through the line of cannons where they briefly caused havoc in the rear of the Russian line before exhaustion, the decimation of their ranks and Russian reinforcements forced them to retreat. Turner meantime, must have ridden, or been carried back down the valley to the British lines, bandaged up and with others was then placed aboard a transport ship bound for the military hospital at Scutari in Turkey. However, he never made it, his wound was too severe; Private George Turner aged 25 years old died aboard ship on 28 October and was probably buried at sea.

There was no mention of the fate of Private Turner in the local papers at the time and it took 120 years for his story to finally make the pages of the Sentinel. It was related by Mr W. R. Baker of Endon, who added, 'I ask your readers to spare a moment’s thought to his memory now when tradition has little meaning and patriotism is an outmoded word I make no apology for thinking that he should not be entirely forgotten.’

There existed, though, another poignant addendum to Turner’s sad tale. Seven months after the battle of Balaclava, the Light Brigade had passed again over the same ground, now deserted of enemy troops and here the upper part of a sabre scabbard, all twisted and mangled, was picked up by Sergeant Major Loy Smith and it became part of his collection of memorabilia. When the collection was put on display in Sheffield in 1981, a card attached to the scabbard’s remains read, ‘This belonged to Private Turner, K.I.A.’

*Despite my best efforts, I have yet to find a trace of a George Turner in the local civil records who fits the available data, raising the possibility that the name is an alias.

Reference: Evening Sentinel, 25 October 1975, p.4; George Loy Smith, A Victorian RSM: From India to the Crimea, p. 132. My thanks to Mr Philip Boys for kindly providing me with background information on Private Turner contained in ‘Lives of the Light Brigade: The E. J. Boys Archive’.

|

| Lance-Sergeant J. D. Baskeyfield VC |

On 19 September, General Urquhart attempted to reach Frost and his men in Arnhem, but the British suffered heavy losses against German armour. Urquhart therefore pulled his men back to Oosterbeek, a suburb of Arnhem, hoping to establish a bridgehead against the river until ground forces arrived. The Paras and South Staffords created a perimeter at the edge of Oosterbeek, bringing in artillery to cover the main roads and snipe German tanks when they came. At 11:15 a.m., eight anti-tank guns from the South Staffords were moved forward, with two of their 6-pounder guns positioned at the T-junction of Benedendorpsweg and Acacialaan to take on any German armour moving in from the north-east, while other guns covered their flank and troops in trenches and nearby buildings prepared to support the gunners and confront any enemy infantry.

In charge of the two guns facing up Acacialaan was 21-year-old Lance-Sergeant John Daniel Baskeyfield of the South Staffords’ Anti-Tank Platoon. Born on 18 November 1922, ‘Jack’ Baskeyfield was the eldest of five children born to Daniel and Minnie Baskeyfield of Burslem. Educated at Burslem St John’s School and Christ Church, Cobridge, for several years he was a choirboy at Cobridge Church. Starting work as an errand boy, he later trained as a butcher and briefly managed a co-op butchers in Pittshill. He was called up for the army in February 1942 and served with the 2nd South Staffords in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy before participating in Operation Market Garden. No stranger to peril, during the North Africa campaign, a glider that Jack was aboard crashed into the sea and he spent 8 hours in the water before being picked up by a launch. Evidently a good soldier, he had achieved the rank of lance-sergeant through merit and during the ferocious battle that would take place around his guns the next day, his ability to lead and inspire those around him would prove him worthy of the rank.

|

| The statue depicting Jack Baskeyfield at Festival Park, Etruria |

Pulling himself away from the wreckage and under intense enemy fire, Jack crawled across the road to the other gun, Corporal Hutton's 6-pounder, the crew of which now lay dead around it. Again, he manned the gun alone, though another soldier tried to crawl across the road to help him, but he was killed almost immediately. Undaunted, Jack carried on, engaging another enemy self-propelled gun that was moving in to attack. He managed to get off two rounds, one of which scored a direct hit on the vehicle, rendering it ineffective, but, sadly, whilst loading for a third shot, he was killed by a shell from a supporting enemy tank.

There is some question over the number or type of ‘kills’ that Jack and his men gained, but there is no disputing that the terrific stand he made inspired nearby troops and bolstered that part of the perimeter. This undoubtedly helped in preventing the Germans from cutting the 1st Airborne Division from the Rhine, across which the survivors of Urquhart’s forces escaped several days later. For by 25 September, the desperate struggle for Arnhem was over, and Major Frost's men had been forced to surrender. Hundreds of soldiers and over 400 Dutch civilians had been killed, thousands more wounded and Arnhem and its suburbs were wrecked and littered with bodies, many mangled beyond recognition. Corporal Raymond Corneby and other captured troops were working to gather up bodies where Baskeyfield and his men had fallen, when he found just such a corpse, a battered, headless body by the wreckage of a gun, which he buried in a nearby garden. From the evidence Corneby found on the body it seems very likely that this was Jack Baskeyfield, whose remains now lie in an unknown grave. His name appears on panel 5 of the CWGC Groesbeek Memorial to the Missing.

Despite his body being lost, Jack's deeds were not forgotten, and word of his bravery spread quickly. A week after the battle, war artist Bryan de Grineau drew a sketch of the action for the Illustrated London News and official reports were made on Baskeyfield's behalf, with the recommendation that he be posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. This was granted, and the London Gazette carried the official citation for his award five days after what would have been his 22nd birthday. This outlined the action and Jack Baskeyfield’s doggedness in carrying out his duty in defending the road junction, his determination to carry on even though badly wounded and it praised ‘his superb fighting spirit’ which inspired all who witnessed his stand. Back home, though his parents and siblings were devastated by the news of his death, they were immensely proud at the news that Jack had been awarded the Victoria Cross. At an investiture at Buckingham Palace on 17 July 1945, Daniel and Minnie Baskeyfield received their son’s medal from King George VI and soon after the war they took a trip to the Netherlands to see where their son had died. Jack Baskeyfield’s VC is today in the keeping of the Staffordshire Regiment Museum at Whittington near Lichfield.

Pride was felt across the Potteries at Jack’s incredible bravery. A memorial fund was set up, a mural was raised in his honour at one of his old schools and his name continues to be used proudly around the city in streets, buildings, an Army Reserve Centre and for a while a local school. In 1966, a local amateur film maker Bill Townley began filming a well-produced cinematic depiction of Jack’s deeds entitled ‘Baskeyfield VC’, which received it’s first public airing in 1969 and is still available to buy on DVD. Official memorials also appeared. A plaque dedicated to the town’s medal winner sits near to Burslem’s war memorial on Swan Bank, but surprisingly the most notable memorial was erected not in Burslem, but at Festival Heights in Etruria. Unveiled in 1990, the twice-life size statue of Jack Baskeyfield sculpted by Steven Whyte and Michael Talbot, has him in action, shell in hand in the act of loading his gun; a brave man, defiant to the end.

On 26 January 1895, 27 year old George Stevenson, a habitual petty criminal and deserter from the British army was shot and mortally wounded in a backroom to a bar in Johannesburg, in Southern Africa, for informing on his fellow criminals after a robbery. The story made news locally as Stevenson, though born in Hixon near Stafford, had grown up in Hanley, where he had turned to a life of crime at a very early age. At the age of ten, after several run-ins with the law, he was sentenced to Werrington Industrial School for four years, where he did seem to turn his life around and in 1882 was released back to his parents. For several years Stevo, as he was known to his friends, worked in his father’s clay pits, then in 1886 aged 18, he joined the army and the next year was posted to Pietermaritzburg in South Africa. Though he stayed in touch with his mother, Stevenson never saw his family or the Potteries again.

At first Stevo enjoyed army life, but garrison duty bored him and at the end of 1889, he deserted and fled to Johannesburg arriving there early in 1890. There he led a brief inglorious life as a thief being quickly caught and sentenced to a year on a chain gang and though he escaped and went on the run he was eventually recaptured and sent to finish his sentence. Shortly after his release in 1893, he fell in with a villain and fellow deserter (from both the army and the Royal Navy) named Jack McLoughlin, who went by the nickname of ‘One-armed Jack’, from having lost his lower left arm during a jailbreak. At first the two men were good friends, but only a few months passed before tattled tales between their respective lovers caused them to have a falling out and they shunned each other for a time. It was only when McLoughlin needed several others to help him with a robbery a few months later that they patched up their differences enough that Stevo could join the gang.

The gang robbed a safe at a railway station in Pretoria, it was a pitiful haul and their troubles started immediately after the robbery when they tried to take the train back to Johannesburg and realised the authorities were onto them. One of the gang stayed in Pretoria, while early in the journey Stevenson got cold feet and quit the train and doubled back. McLoughlin jumped through a window to escape while the train was in motion, leaving one man on the train who was arrested in Johannesburg. Stevenson and the gang member in Pretoria were also quickly caught. In custody and fearful of returning to prison, when he heard that another of the men was about to inform on them, Stevo got in first and told all to the authorities, naming McLoughlin as the ringleader. Stevenson avoided imprisonment as a result, but he knew that his life was now in danger as McLoughlin, who remained at large, was a vindictive man who hated informers.

Stevenson and his lover Sarah Fredericks fled Johannesburg for a time, but foolishly drifted back into town a few weeks later and by January 1895, they were living out of a room at the back of the Red Lion bar close to their old haunts. With no sign of McLoughlin, Stevo thought he was safe, but on the 26 January he learnt that One-armed Jack was in town looking for him. Stevo and Fredericks retreated to their room hoping he would not find them. A few hours later, though, there was a knock at the door. Expecting a visitor Fredericks opened the door, only to find that it was McLoughlin, who had tracked them down. Brushing Fredericks aside, One-armed Jack then pulled a gun and shot Stevenson who was sitting on the bed, mortally wounding him before making his escape. Pursued by an angry mob, McLoughlin then shot and killed another young man who he thought was trying to stop him and fled into the night going on the run once more. Back at the Red Lion meanwhile, Stevenson lingered for a time, but presently died from his wound. His last request to Fredericks was that she send his ring back to his mother in the Potteries.

McLoughlin escaped and eventually fled South Africa, first to India, but later back to Australia and it was there in 1908 that he was arrested. When the Australian authorities realised McLoughlin was wanted for murder he was extradited back to South Africa where he was quickly sent to trial, found guilty of the double killing and hung in February 1909.

Reference: Charles Van Onselen, Showdown at the Red Lion: The Life and Times of Jack McLoughlin, pp. 288-342. Staffordshire Sentinel, 22 December 1877; 19 June 1878, p. 3; 28 October 1878, p. 3.

|

| British Mounted Infantry and Zulus at the Battle of Gingindlovu |

Newspaper accounts of the local soldiers involved in the battle of Isandlwana that trickled back to the Potteries in early 1879 occasionally mentioned a Private Frederick Butler of the 2/24th Foot who had been seconded to the Imperial Mounted Infantry. Initial reports in early March indicated that he was a casualty, but these were wrong. In a subsequent report in the Sentinel on 5th April 1879, his father William, the publican of the Bell and Bear Inn, Snow Hill, Shelton, noted that his son had survived and that the family had received a letter from Frederick detailing the fighting he had seen, but this potentially interesting letter was never published in the paper, leaving the readers to wonder at what his story may have been. Frederick was alive, that much is true, but he lived largely because he was nowhere near to Isandlwana when the battle occurred.

1199 Private Frederick Butler, 2/24th and 2nd Squadron Imperial Mounted Infantry

Frederick Butler was born in 1858 in Alsager, Cheshire, the second of five children born to William Butler and Ann nee Melbourne. By 1861, the family had moved to the Potteries where William became the landlord of the Bell and Bear Inn, Snow Hill, Shelton. Fred's mother died in 1869 and later that same year his father remarried to Sarah Lloyd, by whom he had two daughters. Fred joined the army in 1877, being assigned to the 2nd battalion 24th Regiment of Foot as 1199 Private Frederick Butler. Later that year he and his battalion were posted to South Africa.

Whilst in South Africa, on 1st September 1878 Private Butler was detached to the Imperial Mounted Infantry. This as the name implies was a mounted force that recruited soldiers from the infantry regiments who had some experience with horses, just as the son of an innkeeper might. Butler was posted to the 2nd Squadron Mounted Infantry under Captain William Sugden (1/24th) being employed as a saddler until 12th September1879, according to the pay and muster rolls of the 2/24th. This squadron was sent to serve with No.1 Column ('the Coastal Column') under Colonel Charles Knight Pearson and was commanded by Captain Percy Barrows of the 19th Hussars. This force was to enter the Zulu kingdom some 50 miles to the east of Lord Chelmsford’s Central Column that would soon fall victim to the Zulu counterattack.

With his unit Butler crossed into Zululand on 11th January and over the next week they made steady progress into the interior. The Coastal Column claimed the honour of first blood as early on 22nd January, the same day that the Centre Column was being cut to pieces at Isandlwana, Pearson's men successfully fought off the first Zulu attack of the war at the battle of Nyezane or Inyezane, and Private Butler as a member of the 2nd Squadron Mounted Infantry doubtless played his part in the fighting there. It seems very likely that when he wrote home it was that battle he was describing and misunderstandings by his family and local reporters perhaps gave rise to the story of him having survived Isandlwana. Without seeing the actual letter he wrote it is hard to say if this was the case, but if Pvt Butler had merely noted in his letter home that he had been in a battle with the Zulus on the 22nd this could have easily led to the confusion. The news of Isandlwana, or 'Isandula' as early reports called it, dominated the news, obscuring Pearson's success 50 miles away. Equally, ‘Inyezane’ (as the battle was originally known) could have been confused with ‘Isandula’

Whatever the case, Private Butler was very much alive and served throughout the rest of the war, probably seeing action again with his unit at the Battle of Gingindlovu (2nd April 1879). Though they were not involved in the climactic battle at Ulundi, the 2nd IMI did take part in the search for the fugitive Zulu King Cetewayo after the battle. Butler also got his name in the local press one more time before returning home when a few brief accounts of local men in Zululand were noted in the Sentinel. In it Butler sang the praises of their much-criticised commander-in-chief.

‘Frederick Butler, son of Mr. Butler, of the Bell and Bear lnn, Shelton, writing on July 13th to his parents, makes special reference to the esteem in which Lord Chelmsford is held by the general body of soldiers at the seat of war, observing that they look upon him as “a brave and reliable man.” He also, speaks the hardships the soldiers have to encounter, but gives also the bright as well the dark side of warfare in Africa.'

Staffordshire Sentinel and Commercial & General Advertiser, Saturday 23rd August 1879. p.4

Butler returned to the 2/24th regiment on 12th September 1879. For his service he was later awarded the South Africa Medal with 1877-78-79 clasp.

After the war Fred Butler remained in the army until the 1880s. After that he returned home to the Potteries and on 23rd August 1888 at Holy Trinity Church, he married Mary Jane Smith. At the time he was residing at 12 Brook Street. The couple would have two children. By 1891 Fred seems to have taken over the running of the Bell and Bear Inn from his father. He may also have joined the local rifle volunteers whose drill hall still stands at the top of College Road, Shelton. In this capacity he got his name in papers yet again in 1889, albeit for all the wrong reasons.

'A DANGEROUS PRACTICE.

RIFLE SHOOTING AT SHELTON.

DAMAGES £20.

At the Hanley County Court on Wednesday, before his Honour Judge Jordan, an action was tried and decided, in which Frank Guildford, an engraver, living in Queen Anne-street, Shelton, sued to recover £50 damages from Fred Butler, William Butler, of the Bell and Bear Inn, Shelton; Sidney Smith, cabinet maker, Piccadilly; and J. W. Ault, sign writer, Snow Hill, for personal injuries.

Mr. Boddam. instructed by Mr G. H. Hunt, appeared on behalf of the plaintiff; and Mr. Ashmall defended. £10 had been paid into Court, with a denial of liability.

Mr. Boddam stated that the action was for damages done to the plaintiff being shot by the defendants. - The plaintiff was engraver, and was in the employ of Mr. Fennell, of Mollart-street, Hanley. the 2nd of Mav the defendants were practising shooting in a garden connected with Cleveland House, which was in the possession of Mr. Butler, of the Bell and Bear Inn. They were shooting with a Morris tube, a species of invention with which persons were in the habit of practising shooting at targets. The tube carried a small bullet to a tremendous distance. The plaintiff at the time was walking down the public road at the rear of Cleveland Gardens, and as he was so walking was shot in the head by a bullet, which he thought he (the learned counsel) could clearly demonstrate was projected by one the defendants. Two operations were found to be necessary to get out the bullet, and plaintiff had to remain away from his work for a fortnight. He had sustained a considerable shock to his system.

The plaintiff stated that about a quarter past one o’clock on the 2nd May he was walking along Lime Kiln Walk with two other persons, when he was hit on the left temple with something. He began to bleed, and found that he had got a hole in his head. Directly afterwards the sound of bullet was heard. It struck some boards near where he was standing, and was afterwards taken out the wood.

His Honour: The bullet hit plaintiff’s head and grazed it ?

Mr. Boddam: No; it went in and stayed there. Luckily for the plaintiff his skull was so thick. (Laughter.)

The plaintiff continued that after seeing the police he went to Mr. Charlesworth who attended him until the end of the month. Mr. Charlesworth took out a portion of the bullet on the 4th May, and the remaining portion on the 20th May.

Mr. Boddam stated that they had any number of admissions of liability.

Mr. Ashmall said his clients were anxious to act generously with the plaintiff.

Mr. J. Charlesworth deposed to extracting the bullet, most of which he took out the 4th May.

His Honour; Let me look at it.

Mr. Boddam: You will see how admirably it was flattened by the gentleman's skull. (Laughter)

His Honour : A good job for him that he had got so thick a one.

Mr. Charlesworth proceeded to say that the bullet was very bright and slightly grooved, from which circumstances he concluded that it had hit something else before striking the plaintiff; that in fact it was a richochet shot. The bullet lay one inch from the point of entrance.

His Honour: Was it in a dangerous position ?

Mr. Charlesworth: Not in very dangerous position. The wound was too high to be very dangerous: it struck on the thick part the skull. There would be no permanent injury.

His Honour observed that the wrong being admitted, the only point for him to consider was the amount damages.

Mr. Ashmall explained that two of the defendants were volunteers. The garden in which they were practising was ninety-five yards in length. There were palings at the bottom of it. On the other side of these palings was plantation twelve yards deep. This was bordered by another fence and beyond it, before the road was reached, was a field 300 yards in length, also bordered by a railing. The guns were sighted for 100 yards, he suggested that this bullet struck one of the trees, from which it glanced and then hit the plaintiff. There was nothing absolutely illegal in what the defendants were doing, and as soon as inquiries came to be made the defendants went so far to say that they would pay any reasonable compensation.

His Honour said it was difficult matter to measure damages in a case of this sort. No doubt whatever that the defendants were engaged in a dangerous pursuit, and had they killed the plaintiff, would, he dared say, have been put upon their trial for manslaughter. The damages sustained by plaintiff were not serious, but still it was a dangerous thing to have bullet sent into his head. He thought that in giving a verdict for £20 and costs, he was giving a very moderate sum indeed.'

Staffordshire Sentinel, Thursday 06 June 1889, p.3

Fred Butler appears to have died quite young, aged 33 in 1891.

References:

Info from Forces War Records and Rorkesdriftvc forum.

Thanks to 1879zuluwar forum members Kate (a.k.a 'gardner1879'), John Young, '90th' and Julian Whybra for further information on Frederick Butler.

In early March 1783, the local economy was in decline and people were going hungry. A poor harvest the year before plus the knock-on economic effects of the American Revolutionary War had caused food to become scarce and prices to rise sharply and a number of food riots broke out in Newcastle and the Potteries as a result. The most serious of these took place around the canal at Etruria and may well have been started by some of Josiah Wedgwood's workers.

|

| A view of Wedgwood's Etruria works from across the canal. From The Life of Josiah Wedgwood (1865) by Eliza Meteyard. |

There had been some trouble in Newcastle for several days and the rioters there seem to have joined or inspired the riot that broke out at Etruria on Friday 7th March. The trouble started when a barge carrying much-needed supplies of cheese and flour moored up at Etruria where the food was to be off-loaded before being distributed around the Potteries. However, at the last moment the barge's owners decided to send the boat on to Manchester. Within a short time of this decision shop owners in Hanley and Shelton heard the news and they in turn informed their angry customers. They had probably heard about the barge's departure from some of Wedgwood's own workers, certainly that suspicion was voiced in a letter written by Josiah Wedgwood junior, son of the famous potter. Later that same day Josiah junior wrote to his father - who was then in London on business - describing how when the news spread about the departing barge, several hundred men women and children had quickly gathered and chased after it along the canal, finally catching up with it at Longport. Believing that the boat had been sent away to increase the scarcity of provisions and thus up the prices even more, the crowd were in a black mood and not to be trifled with, so when they found that the bargee would not pull the boat over one of the crowd leapt aboard to tackle him. The boatman immediately cut the tow rope and slashed at the man with his knife and voices from the crowd on the towpath called out “Put him in the canal.” A ducking may well have been the man's fate had not another bargee come to his rescue and he had been able to escape onto another craft, albeit leaving his own barge in the hands of the mob as he did so.

The captured boat was then hauled it back to Etruria in triumph and by late afternoon was tied up alongside Wedgwood's Etruria works where the crowd unloaded the cargo into the factory's crate shop. Most of the rioters then went home meaning to return the next day for distribution of the goods. In the meantime a few men were set as guards. At about 7.30 that evening four of these sauntered up to Etruria Hall and asked for something to eat and drink while they were on watch. Another of the Wedgwood children, Josiah's older brother, 17 year old John went to them and stood talking with them for a time then too did their mother Sarah Wedgwood who also spoke with them for a while before the men went off. The nervousness of the Wedgwood household at this point is, evident in young Josiah's hasty missive to his father, but the family were not bothered any further that evening and at breakfast the next day things were still quiet.

A considered account of what happened next is difficult to come by, certainly none seem to have been carried by newspapers of the time. However, two anonymous letters were circulated by the press which – though they vary in details – give a rough idea of how events unfolded thereafter.

On the Saturday morning the crowd gathered back at the canal side and some of the goods seized the day before were sold off at what were considered by the crowd to be more reasonable prices. One of the letters states that this was at two-thirds the normal price, while sometimes the goods were given away. The meagre proceeds were then handed over to the disgruntled owners of the captive barge. The authorities meanwhile had taken steps to deal with the rioters. An express message had been sent to Lichfield asking for some companies of the Staffordshire Militia to come to their aid. Closer at hand, though, were a company of the Carmarthen Militia who that day had arrived in Newcastle on their way back to Wales. Due to the troubles in Newcastle itself and now in Etruria, the commanding officer was asked if he could help in dealing with the rioters. He agreed, and the force put itself at the disposal of the local magistrates who now had the job of quelling the disturbances.

Some justices went to meet with the mob still gathered around the captured boat, but the Militia were kept at a distance while the officials tried to settle matters peacefully. Here the letters are at odds with one another, one stating that all efforts to get the mob to disperse, including getting the master potters (whose workers formed the bulk of the mob) to try and influence them, but to no avail, while the other letter states that the magistrates' efforts were a success and that the mob agreed to leave, providing the boat was left where it was. Judging by the fact that several days later the mob was demanding the return of the boat the latter seems the most likely state of affairs, but the details still remain confused.

Nothing of great significance seems to have happened on the Sunday, though some of the local manufacturers and officials held a crisis meeting at Newcastle to discuss how best to calm the situation down and deal with the mob. A subscription was entered into perhaps to placate the rioters, Josiah Wedgwood's son John was present at the meeting and donated £10 to the fund. But after the quiet Sunday, Monday saw a return to the stand-off of previous days as the mob gathered at Etruria once more. This time they were in a far more bullish mood and sent messengers to the magistrates outlining their demands, namely to have the boat delivered back to them and its contents sold there.

After a quiet Sunday, Monday saw a return to the stand-off as the mob gathered once more, this time outside Billington's (probably the premises of Richard Billington, who carted coals for Wedgwood and rented 38 acres of the Etruria estate), where there was a meeting of the master potters and several officials. These included John Wedgwood in his father's stead, Dr Falkener of Lichfield, Mr Ing and Mr John Sneyd of Belmont (a neighbour of the Wedgwoods), who harangued the mob on their bad behaviour and the detrimental effect it would have on the price of corn, as too did John Wedgwood and Major Walter Sneyd of the Staffordshire Militia. The latter was there at the head of a detachment of the Staffordshire Militia, who stood by ready if needed. The masters and officials though still hoped that the rioters would listen to reason and a generous subscription was again raised, John Wedgwood giving £20 this time. The mob, though, did not accept this graciously remarking caustically that the money would not have been provided had they not caused trouble and made the manufacturers sit up and pay attention. They continued calling for the boat to be returned to them and the corn to be sold on fairly. Their demands became so loud and threatening that the Riot Act was read out and the mob was told that if they did not disperse to their homes in an hour's time, that the Militia would be ordered to fire on them. The crowd, though, were defiant, jeering that the militia men dared not fire on them and that if they did then the rioters would attack and destroy Keele Hall, the ancestral home of the Sneyd family of Major Sneyd was the current heir. According to some accounts the rioters also put their women and children at the front confident that the soldiers could not fire on them.

Despite this, after the hour had passed, the chief magistrate Dr Falkener was apparently on the verge of ordering the nervous militiamen to fire, when two of the rioters accidently fell down and made him pause and consider his actions. One of the Sneyds, huzzaring as he did so, got about 30 of the men to follow him, intending perhaps to charge the mob, but his effort was thwarted by women in the crowd who called out, “Nay, nay, that wunna do, that wunna do.” and embarrassed by the mocking cries the militiamen baulked, turned back and left the crowd alone. Unable or unwilling to take firm action, the officials agreed that the corn taken in the boat should be sold on at a fair price. And for now that was that and the crowd had their way. The magistrates, though, were now determined to make the leaders of the riot pay for the trouble they had caused and to bring the disturbances to an end once and for all.

Two of the ringleaders of the mob had been quickly identified as Stephen Barlow and Joseph Boulton. According to report, Barlow was born in Hanley Green, was aged about 38 and seems to have had a chequered history prior to the riots, having apparently served in the Staffordshire Militia, but had been drummed out for bad behaviour. He may also have had previous with the law as records show that four years earlier at the Epiphany Assizes at Stafford of 1779, one Stephen Barlow was in court for some unspecified crime he had committed in Penkridge. At some point he had married and by 1783 was the father of four small children and was living in Etruria. The authorities certainly knew where to look for him and that night after the riot, magistrates and constables converged on his house. On hearing the men at the door, Barlow quit his bed naked and attempted to escape by climbing up the chimney. He probably would have got away except that in his haste he dislodged some bricks and when his pursuers came out to see what was happening they caught sight of him hiding on the roof behind the chimney stack. When he was brought down, Barlow refused to get dressed and though it was a cold night suffered himself to be transported stark naked all the way from Etruria to Newcastle. After subsequently being taken to Stafford Gaol, Stephen Barlow was held there until his trial.

So too was Joseph Boulton, but he remains a shadowy figure in this drama as nothing seems to be known of his background. Beyond noting that two ringleaders had been captured at home that night and sent to Stafford gaol, his name was not mentioned in contemporary newspapers, though John Wedgwood who was at Stafford to witness the trial wrote to his father in London and noted that the man had been acquitted by the court. Stephen Barlow, on the other hand was not so lucky. The judge in summing up at the trial on 15th March, detailed Barlow's offence and laid out the law regarding riots in the clear and clinical manner of the Riot Act. “That all persons to the number of twelve or more, who remain in any place in a tumultuous manner after proclamation has been made for the space of one hour, subject themselves to an indictment for capital felony. “ In other words, the death sentence.

The message this sent out was clear, namely those hundreds who had assembled and been involved in the rioting on 10th March, most of whom had since either fled the area or had thus far escaped detection, were just as guilty as Barlow and could expect the same treatment if caught and convicted. Barlow meanwhile was sentenced to death without a quibble and on Monday 17th March 1783, exactly a week after the riot, at Sandyford near Stafford, he was escorted to the gallows by a body of militia and there he was hung by the neck until he was dead. His body was then returned to the Potteries and buried locally two days later.

It had been a startlingly quick chain of events which did indeed have the desired effect quelling any further disturbances, but it perhaps shocked many law-abiding citizens too, disturbed by such arbitrary use of the law. Looking back from over half a century later even local historian John Ward - who as a solicitor had very little sympathy with rioters – seems to have been taken aback by this blatant show trial. Writing about Stephen Barlow, he noted that he 'became a victim rather to the public safety, than to the heinousness of his crime.' According to some accounts Barlow was not the only victim, as more than one paper reported briefly that following the execution, Barlow's wife hung herself in despair.

Josiah Wedgwood though was not so understanding. The danger the riot had presented to his family, estate and pot bank had shaken him and being a noted disciplinarian where his own workforce was concerned, the likelihood that many of them had been involved in the troubles doubtless rankled. On returning to the Potteries and hearing in detail what had gone on, Wedgwood felt compelled to put pen to paper and produced a short tract entitled An Address to the Young Inhabitants of the Pottery in which he hoped to quell any future disturbances by attempting to explain the wrong-headedness of the rioters and to examine and dismiss their supposed grievances. Though couched as a well-meaning sermon to soothe young minds, the piece arguably comes across as being rather sanctimonious given the recent circumstances; the musings of a rich man offering up self-serving arguments to poor people who simply wanted food.

Reference: John Ward, The Borough of Stoke-Upon-Trent, pp. 445-446; Ann Finer and George Savage (Eds.), The Selected Letters of Josiah Wedgwood p.268: Correspondence of Josiah Wedgwood, Vol. 3, pp. 8-9; Derby Mercury, Thursday 13 March 1783, p.3; Cumberland Pacquet and Ware's Whitehaven Advertiser, Tuesday 25 March 1783, p.3; Manchester Mercury, Tuesday 25 March 1783, p.1; Kentish Gazette, Saturday 29 March 1783, p.3; Northampton Mercury, Monday 24 March 1783, p.3; Stamford Mercury, Thursday 27 March 1783, p.2; Ipswich Journal, Saturday 22 March 1783, p.1; Hereford Journal, Thursday 3 April 1783, p.3.

Ken Ray, a long-time researcher into the lives of local soldiers has assembled an impressive list of North Staffordshire men who served in the Napoleonic Wars, the Crimea and the numerous colonial conflicts Britain participated in during the 19th and early 20th centuries. He has very kindly given me access to some of his documents which chart the lives and careers of ordinary men from the region who might otherwise have been forgotten. This is one of those stories...

. . . .

Private Philip Yates, Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (Oxford Blues)

Napoleonic Wars

|

| The Life Guards and Royal Horse Guards (foreground) at Waterloo |

After Waterloo and Napoleon's abdication, the Royal Horse Guards remained in France until 1816, when they returned to their base at Windsor and the rest of Private Yates' service was at home. On his discharge from the army on 5th February 1827, Yates was described as being 43 years old, 5' 10½” tall, with brown hair, grey eyes and a fresh complexion; his conduct as a soldier had been good. The reason for his discharge was due to length of service and amounted to 22 years and 43 days with the Colours, plus the 2 extra years service granted to all Waterloo veterans.

Yates returned to the Potteries after his discharge, travelling from Windsor to Hanley Green, where he picked up the threads of his old life, helped on by a Chelsea pension. Five years later on 24th June 1832, he married widow Elizabeth Pope (possibly nee Orton) in Hanley. In 1841 they were living in Brunswick Street, Shelton. Philip was back working as a glazier, Elizabeth's trade is hard to read as too is that of her 15 year old son from her previous marriage, John Pope, though he may have been a pottery packer; the fourth member of the household was Philip and Elizabeth's eight year old daughter Elizabeth. On a personal note, when I looked at the 1841 census entry, I was surprised and pleased to discover that Philip Yates and his family lived only two doors away from my great, great, great grandparents Thomas and Ann Cooper and their family.

One Philip Yates died in 1847 aged 66 and was buried on 26th December 1847. He had lived long enough to apply for the Military General Service Medal, as it was awarded with the two clasps for his Peninsula War service.

Reference: UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949, Battle of Waterloo 1815, p.23; UK, Military Campaign Medal and Award Rolls, 1793-1949: Napoleonic Wars 1793-1815, p.193; UK, Waterloo Medal Roll, 1815; UK, Royal Hospital, Chelsea: Regimental Registers of Pensioners, 1713-1882, p.58; WO97 Royal Hospital Chelsea: Soldiers' Service Documents;1841 census for Shelton, Stoke-on-Trent.

|

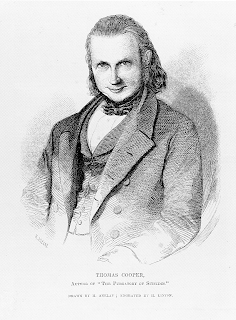

| Thomas Cooper, the Chartist whose fiery speeches sparked the riots. |

The confrontation took place on 16th August 1842. After a day and night of rioting and looting, early in the morning of the 16th crowds began to gather once more on streets of the Potteries. Of the five towns which had suffered in the previous day's rioting, Hanley had been hit the worst. Plumes of heavy fire smoke curled up from either end of the town and the streets were filled with debris. The parsonage was a smouldering ruin and at the top of Pall Mall, Albion House home of local magistrate William Parker had been reduced to a charred and broken shell. On the streets of the town by 7 o'clock a crowd of 400 to 500 people had gathered and were being addressed by two of the local Chartist leaders, young William Ellis and John Richards, the elder statesman of Potteries Chartism. Ellis was urging the crowd not to give up the struggle until the People's Charter became the law of the land. According to witnesses, though, it was the normally mild-mannered Richards who was more to the point. "Now my lads," he said, "we have got the parson's house down, we must have the churches down, for if we lose this day, we lose the day forever." Ellis then spoke again and urged the crowd to go to Burslem to join the crowd there. They were expecting to meet up with a large crowd who were coming to the Potteries from Leek and extend the rioting even further. By 9 o'clock, with shouts of "Now lads for Burslem" and "Now to business", the Hanley mob began marching north.

From Hanley to Burslem is a steady half hour walk for a healthy man and as they entered the town at about 9.30am, the crowd were singing a song that Thomas Cooper had taught them, "... the lion of freedom's let loose from his den, and we'll rally round him again and again." On their arrival in the town a part of the mob barged into George Inn which had only ten days earlier been attacked by outraged strikers and suffered substantial damage. To try and avoid further trouble, the owner of the Inn, Mr Barlow tried to buy the rioters off by giving them a shilling each; some of this was in half crowns and a dispute arose at the door as to the division of it. By this time the greater part of the mob had arrived and they immediately rushed in and filled the house. Mr Barlow had taken the precaution to remove the bulk of his cash; there was however £14 in coppers wrapped up in parcels of five shillings, which were all taken. Numerous bottles of wine, whisky and rum was also stolen, and the taps attached to the beer kegs were left running. Prominent amongst those who conducted this raid was George 'Cogsey Nelly' Colclough, a local lout who had flitted from one town to another the previous day, joining in with the burning and looting wherever he went. Like a moth to the flame he had followed the trouble back to his native Hanley and now thought to export his brand of local thuggery to the Mother Town. But the invasion of the inn did not go unopposed, for while the mob had previously only faced outnumbered police constables, they now found that they were in a town containing a small but formidable force of regular soldiers. They were surprised by a sergeant of dragoons and one or two other soldiers who were billeted at the inn, who hearing the noise, rushed into the bar and lobby to confront the troublemakers. Being in their undress uniforms they only had their swords to hand, but undaunted, the sergeant immediately drew his sword and began to cutting and swatting at the looters and in a few minutes the house was cleared. On being forced back into the street, the mob vented their anger by throwing stones at the windows, and in a very short time all the newly fitted glass was smashed and the house soon presented the same dilapidated appearance as it did after the attack in the night of the 6th.

|

| The Leopard Inn, Burslem. |

The mood in the town had grown increasingly ugly with the arrival of the soldiers and Captain Powys knew that the crowd of people from Leek were even now on the outskirts of the town. If the two mobs joined up and went unopposed Burslem might well be utterly wrecked, so Powys decided that it was now time to restore law and order before things got completely out of hand.

|

| An officer of the 2nd Dragoon Guards in 1842. The helmet would have lacked the black plume while on active duty. |

By now it was getting towards noon and despite the best efforts of Captain Powys and the soldiers, the streets were still full of people. Some had climbed onto the roof of the Town Hall and the covered market, from where they threw stones at the troops and special constables. Powys, increasingly alarmed that the situation might escalate to the point where he might have to use the soldiers more forcefully, was repeatedly seen riding up to the crowds and calling out that the Riot Act had been read and urging people to return to their homes. He was joined in his efforts by others including an Irish naval officer, 41 year old Captain William Bunbury McClintock, who had come to town to meet his friend Major Trench, only to find himself in the eye of a storm. McClintock now rode back and forth from where the bulk of the troops were gathered by the Leopard Inn to check on what the crowds were doing. He saw 'a vast concourse of people in the Hanley Road, and a dense mob on the Smallthorne Road - the latter were accompanied by a band of music. I returned again to the troop, and told Captain Powys there would soon be bloody work.'

Word quickly spread, to the delight of the rioters in the town that the Leek mob of between 4,000 to 5,000 people was advancing down Smallthorne Road and they began moving up Chapel Square to meet them. As McClintock had noted, at the head of the crowd marched a band playing 'See the Conquering Hero Comes' preceded by a large number of men and boys shouting and waving makeshift weapons overhead, all of which could be clearly seen from Market Square. Captain Powys described it as 'the most tumultuous and violent mob which I have ever seen assembled, having seen many riots in the country and in London." He guessed that a clash was now inevitable and barely three minutes after McClintock had ridden back to the troop, Powys ordered Major Trench to move the troop forward to meet the crowd and he formed his dragoons up in sections diagonally across the road from the Big House to the Post office, so cutting the newcomers off from the bulk of the Potteries' mob in the Market Square. The special constables, meantime, closed up nervously behind the cavalry, among them local manufacturer Joseph Edge and his friend Samuel Cork. They looked so alarmed at this point that a kindly lady watching the action from a nearby house sent her servant over with a glass of wine for them both, hoping that the drinks would revive their spirits.

They needed it, for by now the fresh crowd was closing on the thin line of soldiers. Captain Powys on horseback was on the left of Major Trench, who with the other officers were in advance of the dragoons. A large crowd was assembled in the area above the Wesleyan chapel, to witness the arrival of the Leek mob. When about eighty or a hundred yards from the spot where the dragoons were stationed, the Leek party began to cheer and those in front waved their bludgeons. As the head of the procession entered the open space, the front ranks turned to the left, with the apparent intention of making their way by the Wesleyan chapel. About twenty or thirty deep of them had got so far when as Captain Powys later recalled, 'Immediately large volleys of stones, and brick ends were thrown by this mob at myself, and also at the military, I being then in the advance. Similar stones were thrown at the same time by the mob coming in the direction from Hanley at the military, myself and also at the special constables.'

By now the situation was intolerable. Stones were being hurled from both sides of the Market Square, striking horses and men alike and rattling over the cobbles. Captain Powys had thus far been the model of restraint, giving the crowd ample opportunities for a peaceful withdrawal, but it was now obvious that they were bent on trouble. Fearing for the safety of the soldiers, special constables and himself, by his own account he felt he had no choice but to use the soldiers to full effect and turning to Major Trench, Powys asked him to get his men ready to open fire. Trench agreed that the situation was getting out of control and gave the appropriate orders. As the soldiers sheathed their swords and primed their carbines, the large crowd moved forward as far as the Big House. The dragoons advanced slightly to counter them and only at the last moment when the front of the crowd was only six or seven yards away from the soldiers did it seem that the rioters saw the line of guns being raised and levelled at them. 'This movement on the part of the soldiers caused a strange movement amongst those in the front of the mob, and a look of terror came over their faces. Another moment and the order "fire" was given' and the rattle of musketry echoed out loud over the town.'

|

| The Big House, Burslem, where troops and rioters clashed. |

The soldiers fired directly into the crowd, not over their heads as some reported, and many bullets found a mark. Standing in front of the large brick wall that then stood in front of the Big House, was a 19 year old shoemaker from Leek named Josiah Heapy. Despite glowing reports from his employer, who later extolled his gentle character and claimed he had been forced to join the crowd, Heapy appears to have been actively engaged in throwing stones at the soldiers, at least, that is, until a musket ball struck him in the temple and blew his brains out against the gate post.

As Heapy's lifeless form slumped to the pavement, in another section of the crowd, a bricklayer named William Garrett got a ball through his back that exited through his neck and he too fell to the ground gravely wounded but he was eventually whisked off to the infirmary. According to reports others were hit, but in the confusion no one stopped to count the casualties, though it has been supposed that some of the wounded were carried off by their friends and died later. A report in the Bolton Chronicle later claimed that the true tally had been three people killed and six wounded, while reports from Leek spoke of numerous wounded being brought back into the town after the riots.

Some in the crowd seem to have been expecting this development, for shortly after the soldiers had fired their volley someone released a number of carrier pigeons which set off in the direction of Manchester. One of these birds was later captured and found to be carrying a note reporting that the mob had been fired on by dragoons and calling for 50,000 workers to join them in the Potteries. Some witnesses also recalled seeing plumes of gun smoke coming from the crowd just before the soldiers fired, though if this was the case, none of the soldiers or special constables were injured.

Most of the mob, though, was just shocked by the gunfire. From his position behind the dragoons, special constable Joseph Edge had watched all this in fascinated horror, as his son later noted: 'such a scene presented itself which we may pray may never be repeated in this good old town. So panic stricken was the mob that the men simply lay down in heaps in their efforts to get away from the cavalry... '

|

| The 2nd Dragoon Guards open fire on the crowd from Leek. |

Having stunned the rioters, the soldiers kept moving forwards and slinging their carbines, they drew their swords and followed by the special constables they charged their horses into the head of the crowd which scattered in panic before them. Immediately, thousands of people began rushing in all directions, many falling over each other in tangled heaps, others leaping through open windows, or into any available hiding place. Apocryphal tales abound. One Joseph Pickford of Leek is said to have taken shelter in a pig sty, much to the annoyance of its porcine occupants, whose squeals threatened to reveal his hiding place. Hundreds more escaped into the adjoining fields. Another story recalled how Thomas Goldstraw, a powerfully built man from Leek and a noted drummer, dropped his drum when the soldiers charged and quickly fled from Burslem back the way he had come, unaware at first that his son who had been nearby at the time had been shot through the thigh and was lying wounded in a field just outside the town. According to the storyteller, Goldstraw junior was later placed on a cart and transported to the surgery of an obliging physician, Dr Wright at Norton-in-the-Moors, who soon had him back on his feet again.

As the military swept past into the Moorland Road, a portion of the mob from the direction of Hanley, rallied and began throwing stones at the body of special constables, who advanced to the conflict in a dense mass, playing away with their truncheons, and completely routed the mob in that quarter. After the soldiers had charged a short distance up the Smallthorne Road, they were halted and recalled: their job was done as the mob, which just before had consisted of five or six thousand people was completely dispersed and the danger to Burslem had passed.

Reference: Staffordshire Mercury, 20 August 1842; Staffordshire Advertiser, 20 August 1842, p.3; John Wilcox Edge ‘Burslem fifty years ago’, quoted in Carmel Dennison’s Burslem:People and Buildings, Buildings and People, (Stoke-on-Trent, 1996), pp. 36-37; Leek: Fifty Years Ago, (Leek, 1887), p.107 and 121.